Bosnia 2024, Journal #1:

Ozren is Not for Sale

2024 Journal

index

Introduction: Meeting the environmental activists

Journal 1:

Ozren is Not for Sale

Journal 2: Pecka

and vicinity: biologists on front line; scandal of coal

Journal 3: The

Pliva River, from the headwaters to the Jajce waterfalls

Journal 4: Coal in Ugljevik; Lithium on Mt. Majevica

Journal 5: With Hajrija Čobo at Mehorić;

Visiting Robert Oroz in Fojnica

Previous journals and articles

To contact Peter in response to these reports or any

of his articles,

click here.

|

Panoramic view of Ozren from

"Naša Maša" Visitor

Center

In

October of 2024, with the support of colleagues in

Bosnia-Herzegovina, I was able to visit several of the most

important centers of environmental resistance. In a few short weeks

I spent time with many of the activists. What follows is an account

of those weeks, and the thoughts and revelations that they prompted.

Mt. Ozren, in the northeastern part of the Serb-controlled entity

the Republika Srpska (RS), is a center of strong resistance to

environmental assault by mining companies—in this case, by the

Australian company Lykos Metals. One of the leaders of the

environmentalist movement on Mt. Ozren is

Zoran Poljašević, whom I interviewed in the spring. Now I had the

opportunity to meet him and some of his colleagues in the

environmental association "Ozrenski Studenac" (Ozren Springs) of

Sočkovac, a small town on Mt. Ozren.

On the first full day of my stay on Ozren, Zoran picked me up and

took me for a leisurely hike up Gostilj. At 733 meters, Gostilj is

not the highest summit on Ozren, but it is the one with the most

wide-open view. It is also one of the few legally protected areas on

the mountain.

My couple-hours' walk with Zoran provided a briefing on his

background; historical information about Ozren; and an update on his

colleagues' activities in the time since I had talked with him in

the spring.

He

had just returned from Brussels, where he spoke at a round table

presentation to the European Parliament. There, he promoted the

cause of environmental preservation and described the mobilization

of his community in opposition to the threat of destruction posed by

mineral prospecting.

During our walk Zoran mentioned to me that he needed to attend an

emergency meeting that evening at 7:00 p.m., so that would have to

be the limit of our visit. The president of the Sočkovac association

had called Zoran and told him there needed to be a meeting, because

he had been called in to talk to the police. This was not

particularly a surprise, since the police do not look upon

environmental activism favorably.

Reaching the top of Gostilj, to the northeast we could see the town

of Boljanić, and a couple of towns slightly farther north, just

across the inter-entity boundary in the Federation. To the northwest

we looked down upon nearby Doboj, in the Republika Srpska (RS)

entity.

Officials from Lykos had held a public meeting earlier in the year

to promote plans to explore for minerals on Ozren, and about 500

activists showed up in protest. They disrupted the meeting and

announced, "The plan for Ozren designates it as a nature park." This

refers to the prostorni plan, the regional spatial plan that

included preservation of the green-forested hills of the mountain,

the clear streams, and the fresh air of the small towns and villages

that populate the place.

Villagers also held a banner that read, "Leave while we're still

polite." After disrupting the meeting by blowing on whistles,

protestors stated, "We only seek for you to do what you said you

were going to do, nothing more or less."

On Gostilj, Zoran showed me the Iva grass, a plant that occupies a

place in the traditional customs of the people of Ozren. One day

each year, people come to Gostilj and harvest this modest little

plant that they use as tea, and which they say has remarkable

healing qualities. On that day, they wear traditional costumes and

host a celebration, complete with dance performances.

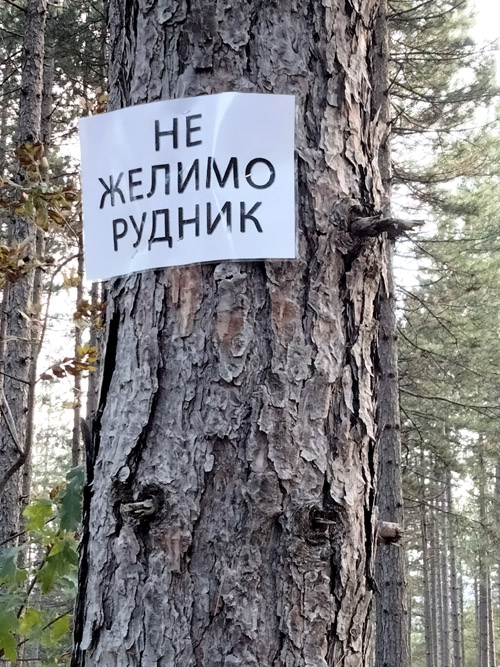

On the path up the hill, Zoran pointed out signs reading, "You're

selling? No one asked us," "Ozren is not for sale," and "We don't

want mines."

Nickel and cobalt are two of the critical raw materials ("CRMs")

identified as crucial to the "green transition" to non-fossil

fuel-based energy sources. Both ores—as is the case with lithium,

copper, and other CRMs, are extremely harmful to the environment

when mined, in spite of claims and promises by the mining companies.

It is not a surprise that the inhabitants of Ozren wish to preserve

the health of their water, air, and soil.

After Gostilj, Zoran took me to a low place among the hills where

two rivers came together. He said that his family used to go

swimming and vacationing there when he was a child. He was born in

1986, just 6 years before the war. Zoran and his family spent a lot

of time there during the war as well, because it was sheltered by

the surrounding hills from artillery fire. The river Prenja runs

through that valley.

The day wore on, and Zoran and I went to dinner. Since it was

approaching 7:00 p.m., Zoran suggested I come along and meet his

colleagues in the Sočkovac association.

It turned out that the story of a police "conversation" had been a

ruse, and Zoran's colleagues had organized the meeting to honor him

for representing their cause before the European Parliament.

When Zoran and I arrived, there were six men present from the

association. At the beginning of the gathering people shook hands

all around, and they presented Zoran with a large wristwatch.. It

was a touching reception that I had not witnessed in my own years of

activist work.

In the midst of this non-meeting, some of the members also took time

to thank me for the essay I had written earlier, which had quickly

been translated into the language that these people call "Serbian."

People said that it was a timely exposé of their situation. Zoran

said that, when journalists come to Ozren, he tells them to read my

article.

Someone was cooking meat in a corner of the modest office. Although

I had just eaten dinner with Zoran, I participated in the feast; it

would have been unfriendly to refrain. There were onions and bread

to accompany the meal, and plenty of rakija (hard brandy) to

wash it down. We were drinking jabukovača, rakija made from

apples. Slobodan, a community leader who was sitting near me,

pointed out Brko, an older gent, and said, "Before the war, in one

season he distilled seven tons of rakija," which I learned meant

7,000 liters—quite an accomplishment.

Brko took care to pass the drink around, and to ensure that it was

consumed. He performed this almost ritualistic gesture three times.

I noticed Zoran looking at me with a bit of concern over the more or

less obligatory alcohol consumption, but I held my own. Meanwhile,

there was the meat: chicken, sausages, suho meso (dried

meat), chops, and more. There was more food than eight men could

possibly have eaten in more than one meal. If it is possible to

overdose on meat, I came pretty close.

I noted that there were no women involved in this gathering. One of

the members said that the women do not come to the meetings, but

they support the resistance and come out en masse for protests and

other actions. Later, I came in contact with other organizations

where the opposite was true, and women were the lead organizers.

A television screen mounted on the wall was set to YouTube where,

among other things, we were able to watch a videos of

Zoran's presentation

in Brussels. There were also clips of the rustic local folk songs,

performed with Bosnian saz and violin.

Amidst the eating and casual YouTube watching, there was relaxed

conversation about the organization's work and goals. Zoran spoke of

the mining company, saying, "Either we will go to jail, or we will

drive them out of our country." Slobodan added, "As long as they are

non-violent with us, we will be non-violent with them."

In the 1990s war, there had been plenty of violence on and around

Ozren. As with the rest of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the mountain ended up

divided between the two resulting "entities," the Croat- and Bosniak-controlled

Federation and the Serb-controlled Republika Srpska. About two

thirds of the mountain remained in the Federation, and the rest in

the RS. But the latter portion is where valuable minerals have been

detected.

Given that rivers flow where they will, and the inter-entity

boundary meanders against all geographical logic, the poisoning that

starts in one entity will inevitably end up in the other. This

potentially brings people who were once on opposite sides of a front

line together against a common enemy. Before, the enemy was defined

by the religion of one's ancestors. The contemporary enemy is

represented by those mining companies that would destroy Ozren's

environment for profit.

"We do not

want a mine!"

I was brought to

Ozren by Denis (not his real name), a Bosniak activist from the nearby town of

Maglaj, who collaborates with regional environmental activists regardless of

their ethnicity. Also traveling with us was Davor Šupuković, from the nearby

village of Fojnica and leader of the environmentalist group "Udruženje Građana

Fojničani" (Citizens' Association of Fojničani). This organization, with a broad

repertoire of activities, is prominent in spearheading research of

biodiversity—an advance tactic in environmental resistance—in many parts of

Bosnia-Herzegovina.

I learned that Davor had fought with the Bosnian Croat army (the Hrvatsko

Vijeće Obrane—Croat Defense Council) during the war, and Denis had come of

age just in time to participate in the defense of his town as part of the

government army of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Armija Republike Bosne i Hercegovine).

Before the three of us drove up Mt. Ozren, we sat in a local restaurant for

lunch. Pointing out the window, Denis showed me the apartment he had lived in

during the war. He also pointed out various hills above the town, explaining

which side had held each location. "They were shooting and bombing us from over

there," he said.

Recounting something I've heard many times before, Denis told me that he had

learned to distinguish each bomb or missile by its sound, which also told him

just how many seconds he and his comrades had to escape. He also told me, "I

must have carried ten dead people out of the streets in those days."

These were the people who were taking me to meet the Serb activists on the

mountain. Zoran

Poljašević

joined us along

the way. We drove up through gentle green, Vermontish hills, past small villages

and lone houses, once stopped by a migrating flock of sheep.

On the way, the four of us stopped at an ancient monastery,

Sveti Nikola na Ozrenu—the

Monastery of St. Nicholas on Mt. Ozren. The monastery was built in the 1500s (or

a couple of centuries earlier, according to folk tradition); for several

centuries the Ottoman occupiers forbade the construction of a bell tower. We

strolled around the well-kept grounds, and spent a few moments meeting the abbot

Gavrilo, a strong opponent of mining on Ozren.

We continued on to a restaurant and visitor center named "Orlovsko

Jezero" (Eagle Lake), not far from Petrovo, the main town of Ozren. We admired

the lake, which sat right below a mountain cliff; it was fed by underground

water coming out from below the mountain.

It was well into the autumn, and there were no other guests. We sat and chatted

with the proprietor, Stanoje, sampling the obligatory rakija. Stanoje greeted us

by launching into a 10-minute presentation of folk etymology which was, for a

while, entertaining if not edifying. Throughout the encounter he demonstrated

that his speaking skills were superior to his listening ability.

Denis sat opposite Stanoje, and we learned that Stanoje had been an artillery

commander in the JNA (Yugoslav National Army) before the breakup of Yugoslavia.

In the 1990s, he performed a similar function in the Serb-controlled

Vojska Republike

Srpske

(Army of Republika Srpska).

Denis and Stanoje had literally been shooting at each other, and here they were,

sitting together and sharing rakija. They questioned each other diplomatically

about their experiences. Denis later told me, "He knew the entire geography of

our area, and all of our own names for the hills where we were fighting."

I had a feeling that I could say that the war was over, but I was not sure.

We traveled to the visitor center "Naša Maša," across the mountain to the west,

near the village of Donja Paklenica. After driving more than a half hour on a

dirt road, we arrived after dark. Davor and Denis left me in the hands of Petar

Tubić, the proprietor of this rustic and welcoming spread in the Ozren hills.

I participated in a meal with Tubić and his family, and went to bed early. The

next morning I had time to explore the place, and to meet Maša and her partner,

Ljubica. These are the two bears for whom the park is named, and they live in a

large fenced-off area on the hillside, under some pine trees. They had been

orphaned as young cubs, and they appear to feel at home in this setting.

Around the

grounds of the visitor center, there are several cabins are available to house

visitors overnight. There are places to hike, a children's playground, and a

pool with a slide. Above the dining lodge, there’s a hill from where you can see

quite a distance in several directions, looking down on the villages and

farmlands.

There were a couple of kid goats wandering around, and Petar arrived in his car,

holding an owl in his arms. There was a fawn in a cage, presumably en route to a

nearby deer sanctuary. There were racoons in a big shed; a black piglet

consorting with one of many kittens, and a pair of llamas. Near

the llamas, there were a couple of peacocks, one male and one female, with their

plumage furled. It was Noah's Ark, without the flood.

Mr. Tubić told me that he had begun building the center ten years earlier. It

looks like he has been busy creating a hub for local visitors and for tourists

from afar. Davor told me that Tubić had fought in the Army of Republika Srpska

during the war, but that today, he welcomes all kinds of visitors, regardless of

ethnicity.

Earlier, Denis had mentioned to me that there was "only" one atrocity committed

by Serb forces upon the population of Maglaj, with some dozen civilians taken

away and killed. This alone is dreadful news—but mild, say, in contrast with

what happened in Srebrenica, Prijedor, and other places. Denis conjectured that,

because of this relatively less bloody history, it has been easier for people

from the opposing sides to get together on some level in the postwar period.

Maša

and Ljubica

I have been

asking myself for some years: When does the postwar period end? Of course, it

depends how you define "postwar." In one sense, it never ends, because the war

will never be un-fought. But "postwar" also refers to people's ongoing response

to that war. In this light, my question could be reinterpreted as asking when

the intensity of people's trauma lessens, and they go forward to thinking about

other things.

For some people, the answer is "never." People's ability to free themselves from

their own burden of victimhood varies depending on what they suffered; what

amount of justice they have seen in the aftermath; and what their own strength

of character allows them to do. But it seems unpredictable.

I have seen people come out of the worst concentration camps and eventually

recognize the necessity and the advantage of living and working with the

"others." Even, sometimes, forgiving. I have seen well-educated people hold

tightly to their sense of injury, and nearly illiterate people find it in

themselves to accept the restoration of ties. There are people in the diaspora,

thousands of miles away, for whom the war is not over. It tends to be the people

closest to each other, across former front lines, who are the quickest to

remember that they have always had, and will continue to have, the same

neighbors.

This reminds me of a time, in 1999, that I visited some refugee return activists

in Doboj, a couple of lawyers who worked for the Coalition for Return. One of

them showed me around the town and took me up a hill to an Ottoman-era fortress.

From there, he pointed out the former front line, and said, "That is where we

were fighting against the Muslim forces."

I asked, "Isn't it strange that you are helping your former enemies to come back

home to Doboj?" He said, "No, I want my old friends to return. It's the

people who stayed in the city and robbed and abused others, who are working to

prevent a return to normal."

This memory, and the experience on Ozren, worked to help me sort out a certain

cognitive dissonance. Since the middle of the war, thirty years ago, I have

spent much time with refugees and displaced people, some of whom were tortured

in concentration camps. I have been to Srebrenica and the ethnically cleansed

towns around Prijedor many times. All the pictures of abuse and torment are

present in my mind.

And at the same time, I can differentiate between the abusers and the ordinary

Serbs who often thought they were fighting to defend themselves. Some of these

people are the ones who are now moving forward. They are, for example, the men

at Sočkovac, one of whom had lost a leg during the war, and another, Slobodan,

who was wounded in the hand.

For these people, I don't know if I can say that the postwar period is over, but

some things are different. They are looking to the future and trying to protect

their land from a dangerous enemy, the corporations who would ravage their

beautiful countryside.

In all this, there is at least the possibility of the new partners—former

enemies—gaining clarity about who their real adversary is and, on top of that,

better understanding what is wrong with the system that guarantees corruption

and profiteering on the land. And finally, these things bring up the question:

How can these good people create a truly vibrant and effective movement to

protect the land?