The defendant,

Slobodan Milosevic, Yugoslavia's former leader, arrives each morning

immaculately groomed. He favors dark blue, wool business suits of

conservative British cut, freshly ironed blue or white cotton dress

shirts with French cuffs, and silk ties, in either vivid maroon or red-white-and-blue

regimental stripes. His black shoes are meticulously polished, his white

hair carefully combed and recently cut. And his black leather Hermes

briefcase is invariably well stuffed in preparation for the day to come,

since he has chosen to appear pro se and is enthusiastically waging his

own defense – a situation that is unusually challenging for both his

judges and his prosecutors,

who must afford him a "fair trial," 1 but seems

very much to the liking of "the Accused," as Milosevic is often termed.

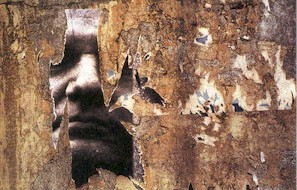

TORN POSTER of Slobodan Milosevic,

Belgrade, 2001

Before going to The Hague, I had followed the

proceedings on' a regular basis, either by watching live webcasts at

3:00 A.M. on the Internet or by downloading trial transcripts when they

appeared on the U.N. website a couple of weeks later. As a form of

reality television, the trial is, to put it plainly, a bit of a slog.

Occasionally, there is a day when a witness gives as good as or better

than he gets under Milosevic's blunt but frequently effective

cross-examination. And many of the so-called crime-based witnesses

(often farmers from tiny villages) tell utterly harrowing stories of

narrow escapes from death squads and of helplessly watching their sons,

daughters, and parents being summarily executed. There have even been a

few insiders (or "co-perpetrators" of Milosevic's "criminal

enterprise," to employ the language of the indictment) who have given

true-life cloak-and-dagger details of how guns and money made their way

from Belgrade to either nationalistic local militias or the sinister

paramilitary groups responsible for most of the decade's worst dirty

work. But ultimately the most interesting challenge in watching the

proceedings is less about trying to sort out the daily testimony as it

is presented by the prosecutors and more about trying to size up

Milosevic as a man – and to ponder the enduring human capacity for evil.

For as you watch Milosevic conducting his own defense, peppering every

witness with minutely detailed questions – regardless of how distant or

unimportant the witness may be to the issue of Milosevic's own part in

events – it is hard to avoid concluding that here is someone (1)

temperamentally incapable of delegating the smallest task, (2) utterly

obsessed with knowing every minor aspect of just about everything, and

(3) remarkably jealous of continually maintaining total control over

whatever he may be doing, whatever it might be. 2 Fortunately

for Milosevic, nothing he says or does in the courtroom when acting as

his own advocate will affect the judges in any way in their final

assessment of the case's "evidence."3 But one can glean clues to his

personality from the pro forma way in which he usually greets the

crime-based witnesses, particularly those whose stories are the

saddest. "I am sorry for what happened to you," he'll say, in a harsh

baritone. Then, virtually without a pause, he'll add, "if it

happened to you."

The International Tribunal for the Prosecution of

Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International

Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia

since 1991 (lCTY) was established in May 1993, after nearly four years

of horrific news coverage fueled an impassioned worldwide public

consensus that it was imperative for the international community to do

something. Almost three years of diplomatic initiatives, U.N.

special reports, various ultimatums, and the imposition of sanctions

had failed to have any appreciable effect on the conflict in Yugoslavia,

or, evidently, to make much of an impression on Yugoslavia's political

and military leaders. When it became clear that neither the UN. nor NATO

was willing to mount an invasion force to impose peace, the

United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 808, setting in

motion the process for establishing an ad hoc tribunal to go after as

criminals those responsible for violations of International Humanitarian

Law in Yugoslavia. 4 It seems unlikely that initially anyone

believed the top leadership of Serbia or Croatia would be brought to

trial. Instead, it was hoped that the threat of prosecution could

be part of a strategy that might put effective pressure on the parties

to start complying in a more wholehearted way with the will of

the international community. But this first tribunal began to take

on a life of its own and paved the way for establishing other IHL courts under the U.N.'s auspices. In November 1994 the Security

Council passed Resolution 955, setting up a second, closely related ad

hoc tribunal to deal with events in Rwanda (with jurisdiction over

appeals from the two tribunals vested in a shared appellate

division). And in the years since, the U.N. has set up other additional

tribunals for East Timor and Sierra Leone. These have been

created on a slightly different model than that of the Yugoslavia

and Rwanda tribunals, the thinking being that justice would be better

served if the courts were located within the country where the conflict

had taken place and if at least some of the judges were nationals of the

country concerned. 5

The ICTY is divided into three wholly separate,

mostly harmonious entities: Chambers; the Office of the

Prosecutor (OTP); and the Registry, whose function is not unlike that

of a Clerk's Office in an American court but which also oversees

many areas of responsibility usually well outside the umbrella

of a national court's operations, such as running the legal-aid

program by which almost all defendants get legal counsel, seeing to all

aspects of the welfare of detainees on trial, and

administering nearly every aspect of the Tribunal's relations

with witnesses, including protection measures and travel. In general,

the prosecutors have received most of the mainstream media's

attention, beginning with Richard Goldstone, the influential and

charismatic South African Constitutional Court justice, who took a leave

of absence from his post to accept an appointment as the Tribunal's

first prosecutor. Goldstone had the shrewd sense to know that if the

Tribunal did not remain in the news, priming the world's indignation,

the will of the international community to see the Tribunal become

operational was almost certain to flag. Chambers and the Registry, which

both tend to be comparatively reticent, may not always see matters from

quite the same viewpoint as the Tribunal's prosecutor, whose statements,

more often than not, tend to be what are quoted by journalists.

During the ten years

the ICTY has been in existence, it has completed, against many less

celebrated defendants, a score of trials that are bound to have lasting

importance, first in establishing the specific judicial facts of what

happened in Yugoslavia between 1991 and 2000 but also (and potentially

of far greater importance) in establishing exactly what kind of conduct

within the context of armed conflict actually constitutes, for example,

Genocide, Crimes Against Humanity, and Grave Breaches of the Geneva

Conventions. 6

In addition, the cases that the Tribunal has decided

are beginning to create a body of specific blackletter law 7

and to provide some general guidance about just who, in addition to

those who have actually been physically involved in committing

atrocities, may be held personally accountable for IHL crimes – either

because crimes were committed on their orders; because they are deemed

accomplices on the basis of their assistance to those directly involved

before, during, or after events; or under some theory of "command

responsibility," 8 which, as a matter of far-reaching legal

precedent, may develop into the Milosevic case's most significant and

controversial issue.

In terms of the sheer quantity of information that is

freely made available, in remarkably rapid time, it is difficult to

complain about the ICTY, which puts any U.S. court to shame. You can

readily access all 30,000 pages of the transcript of the trial's first

eighteen months (though a comparatively small number of pages are

redacted to preserve the confidentiality of "protected witnesses," who

are believed to be in some imminent personal danger for coming to

testify at trial) as well as the half-dozen decisions made by the

Tribunal's appellate chamber in the case, especially those from January

and February 2002, which determined that Milosevic's trial would be held

in a single long proceeding instead of being divided into two shorter

ones, as originally planned. You can obtain a copy of the three-part,

163-page indictment, and with it the prosecutors' initial 50-page

pretrial brief concerning the conflict in Kosovo between January and

June 1999 as well as their 306-page pretrial brief concerning earlier

conflicts in Croatia and Bosnia between 1991 and 1995.

Also available are any

of roughly 200 decisions and orders that the Milosevic trial court has

already issued, some on comparatively minor questions such as

scheduling but many others of crucial importance (such as that

concerning the events contributing to Yugoslavia's disintegration, which

the court has already decided to accept as "adjudicated facts"). Then

there are the judgments of other Tribunal cases. Among the most

important of these is Prosecutor v. Dusko Tadic, decided

in May 1997. Tadic, a zealous Bosnian Serb nationalist, was a small-town

cafe owner who worked as a policeman following the Serb takeover of the

Prijedor District in 1992. During his off-hours, he was a regular

visitor to the three detention camps in the area – Omarska, Keraterm,

and Trnopolje – and participated on numerous occasions in sadistic

beatings and torture of the mainly Muslim inmates of Omarska, the most

notorious of the three camps. He was also involved in the local

"cleansing" campaign, though it is unclear to what extent. The case

remains important to tribunal jurisprudence because it dealt with such

fundamental issues as the "legality" of the Tribunal's creation, the

logic of its jurisdiction, and the protection of witnesses. The Tribunal

also had to determine, for the first time, the basic narrative of what

had happened in Yugoslavia. 9

The problem for anyone

attempting to follow the Milosevic trial is that institutional

"transparency" does not necessarily imply that whatever is made

available to the public is also readily intelligible. The daunting

volume of what is available can seem anything but helpful if you are

seeking to make some general sense of the Tribunal's work and mission as a whole, and particularly

if you are trying to understand where the enterprise of international

criminal justice might be going. I suspected there was much about the

current rapid development of this area of law that I was failing to

grasp, at least beyond a general sense that its importance had been

growing at a surprising rate and that the Yugoslavia Tribunal had been

a catalyst. The only thing to do was to visit The Hague, where the

Tribunal is located, and see if any of the people who worked there would

speak with me. My hope was that if I could get a handle on some of the

more practical concerns in the decision to try Milosevic, I might begin

to get some sense of the world's future prospects for bringing its many

other Milosevics to justice.

II

A criminal trial is anything but a pure search for

truth. When defense attorneys represent guilty clients – as most do

most of the time – their responsibility is to try, by all fair

and ethical means, to prevent the truth about their client's

guilt from emerging.

–

Alan Dershowitz,

Reasonable Doubts (1996)

|

In the week before my departure I was

determined to seek out at least a few of the many Americans who had

spent time working at the Tribunal. Like other organs of the United

Nations, the rules that apply to the ICTY provide that no two of the

current sixteen permanent judges may be nationals of the same country.

Once I reached The Hague, I hoped, might be able meet the current

American judge at the Tribunal, Theodor Meron, a distinguished scholar

who has taught International Humanitarian Law for many years at the NYU

law school. But since a number of people I had spoken to had claimed

that the Tribunal's existence, at least during its early years, had

been possible only because of strong – albeit far from unanimous – behind-the-scenes U.S. support (especially from Madeleine Albright,

first at the U.N. and later as secretary of state), I was also,

accordingly, eager to meet Meron's American predecessors. The most

recent had been Patricia Wald, for twenty years one of the most

respected judges of the Washington, D.C., Federal Court of Appeals.

Before Wald, there had been Gabrielle Kirk McDonald, a former federal

court trial judge from Texas, who had been one of the first eleven

judges appointed to the Tribunal in 1993 as it began operations. Like

Meron, McDonald had been president of the Tribunal (from 1997 to 1999),

which gave me ample reason to hope her overview and knowledge of the

first years would be enlightening. 10

Since McDonald was

coming to New York for a few days, she agreed to lunch, suggesting that

the dining room of the Regency Hotel on Park Avenue, called The Library,

was both quiet and congenial at midday. I knew comparatively little

about McDonald, except that much of her career had been spent as a top

civil-rights litigator in private practice in Houston, specializing in

class-action lawsuits, and that when she had been appointed to the U.S.

District Court in 1979, at the tender age of thirty-seven, she was only

the third African-American woman to be appointed to the federal bench,

and the first from Texas. Since I had worked as a law clerk, after

graduating from the Yale law school in the early 1980s, I hoped that my

background might help me avoid at least a little of the underlying

condescension that experts usually find unavoidable in their

conversations with lay people about specialized subjects.

The Library, as it

turned out, was aptly named if your idea of libraries includes a large

color television (with the sound turned down, tuned to CNN) and you

regard books with the disdain implicit in the professional decorator's

terminology, which refers to them as "furniture." Still, it was, as

McDonald had said, the perfect setting for conversation. While I waited,

Saddam Hussein flashed on the screen above me and mute commentators

standing in front of brightly colored

maps of the Middle East tried to explain to viewers

where in a general way Iraq was located. 11

McDonald is tall and slim and possessed of an almost

offhand elegance. The hint of cultivated Texas mixed into her accent

gives her voice an agreeable music. I asked about the Tribunal's first

years, and she told me that the key had been the remarkable enthusiasm

of the small and very able group who had taken posts at the start.

Nearly everyone involved, she explained, believed that they were part of

an "important and noble enterprise" they were determined to make work.

When she'd first arrived, the Tribunal had only the temporary use of a

small office in the Peace Palace 12 (where the U.N.'s

International Court of Justice is based), and a lengthy search for a

suitable prosecutor had been the first major obstacle to be faced. Ramon Escovar-Salom, the public prosecutor of Venezuela, had accepted the job

(in October 1993) but changed his mind less than four months later.

Accordingly, with no immediate prospects for any defendants being

transferred into the custody of the Tribunal, the group of eleven

judges, including McDonald, had begun their work by drafting detailed

rules of procedure, which would embody contemporary international

standards for fair trials and humane detention of persons accused of

crimes. This was a momentous undertaking. The only predecessors of the

Tribunal had been the Nuremberg proceedings (along with a string of

important war-crimes trials that followed, held in Germany under

American auspices between 1947 and 1949) and a trial somewhat similar to

Nuremberg held in Tokyo of Japanese leaders. In both of these cases, the

rules of procedure adopted had been fairly cursory and, at least at the

Tokyo tribunal, had vitiated any claim to basic trial fairness. 13

McDonald enlisted the help of the U.S. Justice Department to produce a

first draft, and although this initial version of the rules seemed a

reasonable starting point to her judicial colleagues – from Italy, Costa

Rica, Nigeria, China, Canada, Australia, Pakistan, Egypt, Malaysia, and

France – their first impression, she admits, was, "It's so American."

As for the length, complexity, and costs of trials at

the Tribunal, a recurring subject of criticism, McDonald pointed out

that, in any international trial, some costs, such as translation of

both documents and live testimony, are obviously unavoidable. 14

We talked about what she had been proud of during her tenure at the

Tribunal. She explained that, although rape – when carried out on a

widespread and systematic basis – had been specifically made part of the

statute that created the Tribunal, and had been defined as a "war

crime," prosecutors had not initially paid much attention to crimes

against civilian women per se. This, said McDonald, is no longer true,

and the Tribunal's cases are increasingly regarded as significant and

pioneering precedent for what is now emerging as a significant

imperative of International Humanitarian Law.

III

Currently, our Tribunal has approximately twenty

investigators for all the crimes over which it has jurisdiction.

. . . This, I believe, speaks volumes for the tremendous problems with which we are

confronted.

–

Judge Antonio Cassese,

president of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former

Yugoslavia, November 14, 1994

|

Whatever your expectations, the anonymous,

three-story, rough white-brick building housing the ICTY is almost

certain to disappoint. The Tribunal's immediate neighborhood, about

half an hour's ride on the Number 10 tram from The Hague's historic

center of cobbled streets, brick churches, bicycle paths, canals, parks,

palaces, small shops, embassies, museums, elegant Old World government

buildings, and understated luxury hotels, is a slightly run-down,

vaguely suburban, mixed-use zone of residential, commercial, and

industrial structures. You might be in nearly any small and dreary city

nearly anywhere in northern Europe.

Originally built in the Churchillplein Plaza as the

corporate headquarters of the Aegon Insurance Company, the ICTY's

building dates from the early 1950s and suggests a grudging admiration

for the neoclassical simplicity of the Italian Fascist period. Probably

the most immediately striking feature of the Churchillplein is not the

Tribunal but the Congress Centrum's football-field-size fountain and the

animated advertising sign hawking stage shows like Disney on

Ice and The Sound of Music. The Tribunal, in contrast, takes

low-key discretion to an extreme, and the only hint of what goes on

inside is an enormous satellite dish atop its roof and the pale blue

U.N. flag hanging listlessly on a flagpole in front of the building's

tall, black iron gateway. It is easy to miss.

In theory, any interested member of the public is allowed to

attend Tribunal trials. But security is tight. You present yourself at a

guardhouse some twenty feet away from the building, show your passport

to a uniformed U.N. officer sitting in a booth, and obtain your blue or

pink ticket, duly stamped with the date and indicating your status as

VIP, Press, or Visitor (or some combination thereof). Then you walk

through a metal detector sensitive enough to be triggered by no more

than the combination of a watch, a small belt buckle, and the metal

eyelets of shoes, so you must empty your pockets and begin the whole

ritual again.

Once inside the

building, you undergo security screening a second time before you are

allowed to go upstairs to the visitors' gallery of Courtroom One, which

is occupied most mornings by the Milosevic trial. There are usually few

spectators present – from less than ten to around fifty, depending on

whether something new or noteworthy is going on. All Tribunal courtrooms

are rigged with cameras in surveillance style, and most offices in the

Tribunal building have televisions that allow access to the court's

closed-circuit system. 15 Almost no one, except the members of

Milosevic's Belgrade defense team, stays for the duration of the

session. At the entrance, you will see a rack of radio transmitters,

and unless you are fluent in English, Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian – "B/C/S," as it is called here, with a nicely politic sense of recent

history – and Albanian, you'll want to take one. Earphones neatly coiled

are to be found at each of the gallery's hundred or so chairs.

Earphones, you soon

realize, are worn by everyone, not just visitors. Although translators

remain unseen at the Tribunal – they occupy a booth with one-way glass

on the left wall of the courtroom – most often it is their voices that

you, the judges, and the prosecutors hear. This is a matter of some

significance, since in a trial setting much has traditionally turned on

a judge's opportunity to experience and assess "the demeanor" of a

witness and how he or she sounds when speaking. 16

The day of my

arrival should have been an especially exciting one to watch. One of the

case's more highly placed political "insiders," officially known at the

time only as "Witness C-061," was beginning the third of eleven days of

, testimony about the founding within Croatia of the separatist Serb statelet of Krajina in the early 1990s. The hope was that Witness C-061

might provide crucial evidence for establishing both Milosevic's

personal involvement as a matter of fact and his "intent" as a matter of

law. The prosecutors contend that the so-called Log Revolution – the

harbinger of the rapid fragmentation of Yugoslavia into increasingly

polarized, antagonistic ethnic groups and a decade of savage conflict – was not a spontaneous grass-roots movement but a carefully planned set

of events, fueled by propaganda and orchestrated on Milosevic's orders – or, at the least, carried on with his knowledge, approval, and help.

Milosevic's control of Serbia's media, and his use of it as an

instrument of state for demoralizing his enemies while bolstering the

morale of combatants, as well as a means of persuading his

constituency, is an important part of the prosecutors' case. In the

event that the trial court decides that Milosevic's propaganda campaign

constituted conduce they deem criminal in nature, a great many thorny

issues about the relationship between a country's press and its

government's war effort will need to, be more squarely faced than they

have been in the past. It is important to bear in mind that prior to and

during Yugoslavia's period of conflict, the rhetoric of Belgrade,

presented to its citizens in the form of news reports and government

intelligence, suggested that Croatia was mounting a campaign of

genocide against all ethnic Serbs, and that the ethnic Muslim population

of both Bosnia and Kosovo were "terrorists" closely allied with such

radical foreign groups as the mujahedeen.

Trials often have been compared to plays, but the

public visitor to virtually any proceeding involving a serious

violation of International Humanitarian Law will experience something

more like a "set visit" to a major Hollywood movie. You will see, even

over the course of several lengthy days, only a small, frequently dull

or mystifying piece of a long and complex story, and unless you've read

the script with care (which is to say, the indictment), you will have

absolutely no idea where the piece you've seen belongs. In the Milosevic

case, the last-minute joinder of three separate indictments has made it

exceedingly difficult for an observer to follow the trial's basic

narrative. It was determined that Kosovo, the first of the three

indictments filed (chronologically, the historic third act of

Milosevic's political career), should be the first part of the

prosecution's case; the case against the accused for crimes committed

in Croatia (Act I) and Bosnia (Act II) would be presented afterward.

Witness C-061 figured at a comparatively early stage in the chronology

of Yugoslavia's breakup, so the idea apparently was to use his

testimony about his role in helping to create and run Krajina, and the

contact he'd had with "Belgrade," to show that Milosevic had instigated

or been an early party to events. Since Milosevic has consistently

claimed that he was defending or supporting his fellow Serbs against

ethnically motivated violence, and not leading a campaign instigated by

Serbs against others, a number of journalists were optimistically

predicting that C-061 might prove to be the case's "smoking gun." Maybe

C-061's testimony wouldn't cause Milosevic to break down in open court

and confess, but it was thought that a face-to-face confrontation

between the two "co-perpetrators" might undermine Milosevic's version of

events. Before the end of his first week on the stand, C-061, in

response to four days of Milosevic's taunting cross-examination, made

the dramatic decision to give up his status as a protected witness and

reveal that he was – as most journalists covering the trial had

assumed – Milan Babic, at various times the president, prime minister,

and foreign-affairs minister of Krajina.

It is difficult to infer exactly what sort of trial

the prosecutors originally hoped to bring. Their indictment against

Milosevic for IHL crimes in Croatia is confined to counts of Crimes

Against Humanity, Grave Breaches of the Geneva Conventions, and

Violations of the Laws or Customs of War. In this indictment, although

fifteen other participants are named in "the joint criminal enterprise,"

Milosevic is the sole defendant, implying, as in fact is the case, an

intention to try him on his own. The Kosovo Indictment, however, names

him and four others as defendants, implying the intention to hold a

trial more like Nuremberg, in which top ministers and military leaders

would share the docket. The Bosnia Indictment, on the other hand, is

much the same as the Croatia Indictment, though an additional count of

Genocide is added. Milosevic's fourteen key co-participants are named in

this indictment, but he is charged as the case's sole defendant. Many of

those who are named in the three indictments, such as General Ratko

Mladic and Radovan Karadzic, have also been charged in other

indictments. Consequently, they are fugitives whom all U.N. member

states are under obligation to arrest and transfer to The Hague if found

within their territory. Others, such as Biljana Plavsic (Karadzic's

successor as president of Bosnia's separatist Serb republic), have

chosen to surrender to the Tribunal – and in Plavsic's case, pursuant to

a plea bargain, she has already pleaded guilty and been sentenced. Still

others, including Croatian president Franjo Tudjman and the notorious

paramilitary leader Arkan, are dead.

Time is probably the

most important recurring issue in the case. And Milosevic's decision to

represent himself, his regular exercising of his "right" to equal time

for cross-examination, and his bouts of chronic illness have in

combination given him a crude but effective strategic advantage. He

almost certainly has concluded that there is little chance he will be

found innocent of all sixty-six counts of the indictments against him,

and realizes that conviction for anyone of them carries the

probability of a long prison term. Since he is now sixty-two years old,

even a moderate sentence would be for all practical purposes a life

sentence. From his point of view; the only thing that will change when

his trial is concluded is his status from that of an accused, presumed

innocent and in detention, to that of a convict serving a prison term.

Accordingly, he has every incentive to drag the trial on for as many

years as possible. Each day Milosevic can fill or have cancelled because

of illness is potentially one day fewer for the prosecutors to present

their case in all its detail. And the net result, already plainly

evident, is that a far less comprehensive case will be made against him

in the end. 17

The case's lead prosecutor, Geoffrey Nice, is a

British barrister with long experience in both criminal cases and

extremely complex civil litigation, and when in court he displays an

easy command of the logic and details of his case, the applicable law,

apposite Tribunal precedent, and the subtleties of the Tribunal's

continuously evolving trial procedure. Moreover, he seems attuned to

the practical wisdom of the old litigator's saying, "It is better to

know the judge than it is to know the law." In more than a year of

watching the case, I have never seen him ruffled in any way by tough

questions from the bench, though he is entirely capable of purposefully

showing his exasperation at rulings he feels unwise or that have not

gone his way. Nice is small, lithe, and dark-haired, and unlike his

"learned colleague" Steven Kay (the barrister usually leading the team

of amici

appointed to raise legal arguments on Milosevic's behalf), Nice does

not wear the barrister's traditional white-powdered wig to court,

though, like everyone else in the room, except the court reporters and

guards, he does wear black robes and the starched white collar, or

"bib." 18 If I have a cavil about Nice, it has little to do with

the substance of his skills or the thoroughness of his preparation and

only to do with his courtroom manner and the style of his advocacy.

Always at pains to cast his argument or request in solicitous terms of

how the OTP might better or more fully be of "assistance" to the bench,

he reminds me of the various head boys I instinctively disliked at

boarding school.

Dermot Groome, the

American lawyer who has most often appeared in court on the prosecution

team, is tall, blond, broad-shouldered, and always well prepared,

poised in direct examination and possessed of a canny ability to zero in

on what of consequence has really been put at issue in the course of

Milosevic's cross-examination. He has been in charge of the Bosnia phase

of the case, and he is skilled at quickly making a few brief, big, and

straightforward points during redirect.

Hildegard

Uertz-Retzlaff, a third principal member of the prosecution team who

regularly appears in court, is addressed by Milosevic as "the Lady on

the Opposite Side," a mix of outward gentlemanliness and pointed

condescension that is clearly meant to be irritating. Since the Croatia

charges are her part of the case, it falls to her, on the morning I

arrive, to examine Witness C-061. Perhaps because English is not her

first language, or because she is from Germany, a civil-law country

where trials are conducted on a non-adversarial basis, she is noticeably

less smooth on her feet than her two colleagues, and her deliberate, step-by-step style is sometimes frustratingly slow. 19 Unlike

Nice, Uertz-Retzlaff can be rattled when things go wrong – and

particularly by the almost thespian displays of pique of presiding judge

Richard May, who clearly sees hurrying matters along as a key part of

his role in the management of trial time.

Judge May is strict but

scrupulously fair, almost preternatural in his understanding of human

weakness and wickedness in every guise, impatient, very rarely fooled,

and as quietly capable a criminal court judge as I have ever seen. Even

Milosevic seems to grudgingly afford him a measure of respect. His

memory and grasp of detail of the case presented thus far is often

tested and displayed, especially when Milosevic on cross-examination

tries to sum up or restate a witness's prior testimony for purposes of

posing a leading question. Whenever May feels Milosevic has crossed the

boundary from recasting data in an advantageous light into genuine

misstatement, he pulls out his handwritten notes, almost instantly

locates the testimony alluded to – from hours, days, or weeks earlier – and corrects Milosevic with verbatim quotation. 20

The two other judges

sitting on the Milosevic case, Patrick Robinson of Jamaica and O-Gon

Kwon of South Korea, also are jurists of impressive prior

accomplishment. Prior to his appointment as a judge of the ICTY,

Robinson devoted much of his legal career to IHL and human-rights

concerns, frequently acting as his country's ambassador and/or

negotiator on treaties. He is also an experienced prosecutor and was

for several years a deputy solicitor general of Jamaica. He is the most

empathetic of the three judges, and his questioning suggests he sees as

paramount the victims' viewpoint as well as that of the criminal

defendants. Of the three judges, he is the most skeptical of Nice's

various proposals to assist the bench and speed up the trial, and the

most consistently solicitous of Milosevic's health. Judge Kwon, the

youngest of the three judges, holds a 1985 graduate law degree from

Harvard and was a rapidly rising judicial star in Korea before his

appointment to the ICTY. Appointed senior judge in the Seoul District in

1999, he was elevated to senior presiding judge in the Taegu High Court

in 2000.

The morning moves

slowly. From the visitors' gallery what appears in transcripts as

several blank redacted pages translates into long idle spells of

pantomime colloquies. Today about fifty Dutch soldiers in uniform are in

the gallery, but it is the group of Milosevic's Belgrade legal

"associates" who catch nearly everyone's attention. This includes three

women who remind me of Charlie's Angels. C-061, like all protected

witnesses, is completely screened off from the gallery. The glass wall

separating the courtroom from the gallery has an accordionlike screen

divided into three sections that extends the entire length of the room.

Although the central section is lowered to block all view of protected

witnesses, the other two are not. Accordingly, even when the court goes

into "closed session" and the feed of microphones, translations, and

cameras is turned off, you can still see most of what is happening.

21

Uertz-Retzlaff has

decided to use C-061 to identify the voices on a series of some fifty

intercepted cellular-phone conversations that the OTP is offering as

evidence of Milosevic's personal involvement in events. Of them all, it

is conversations between Milosevic and Radovan Karadzic, the long-term

leader of the breakaway Bosnian Serb republic, who is under indictment

and still at large, about which anticipation is keenest. Since Witness

C-061 was not a participant in the calls, was not physically present to

overhear them when they took place, and was not the person who recorded

them, the Milosevic amici have raised objections, and the court has

invited each of the parties to orally amplify their various prior

written "submissions" about the admissibility of the intercepts. After

a Ms. Higgins speaks on behalf of the amici, it is Milosevic's turn. He

contends in forceful terms that the intercepts were illegally obtained

and perhaps subsequently doctored, then asks how the witness can

possibly "confirm the authenticity of conversations between me and a

third person." Nice, however, has the final word. He argues that, as a

general matter, it makes better sense for evidence under challenge in

this way to be "provisionally admitted" when it is clear that

more evidence will be forthcoming by which the first piece of evidence

can be properly weighed and its admissibility and value assessed.

When the trial resumes

after a twenty minute recess (taken so that the members of the bench

can discuss in chambers how they will proceed), Judge May announces that

the court deems the intercept recordings admissible on "a prima facie"

basis, but stresses that at a later time the OTP will have to submit

further evidence about the circumstances under which the recordings

were made. The court seems to be conceding, at least tacitly, that it

may have to face the question of to what extent the initial "legality"

of what is essentially a wiretap during conditions of conflict or war

should be a factor in either admitting such evidence in the first place

or assessing its reliability or "weight" once admitted. 22

Unfortunately for the

gallery, it soon becomes clear that Uertz-Retzlaff does not propose to

play the tapes in their entirety in open court, since, she explains,

"that would take approximately two days." Instead, she suggests that it

would be more expeditious to play just enough of several tapes so that

the voices can be identified; and that instead of having the witness

listen to each intercept – something he has obviously already done –

she will submit a written "declaration" made by C-061 in the course of

his prior two-day listening session. This she requests be placed "under

seal," which is to say, not as part of the public record.

Unfortunately for

Uertz-Retzlaff, nothing proceeds smoothly. The "index of intercepts"

she has prepared to "assist" the bench is for some minutes a source of

confusion, and once she is allowed to begin playing the first tape, the

sound quality is so poor that Witness C-061 complains about the

"interference in the headphones." I glance at Milosevic, who seems

thoroughly pleased by her discomfort.

The short excerpt that

is played proves to be fairly dull; it sounds like any conversation

between two political leaders who, wary of being overheard, have learned

to express their thoughts in a language that is on its face pointedly

unobjectionable.

|

Notes

1

As the American, British, French, and Russian architects of the famous

Nazi war-crimes trials held at Nuremberg in 1945 discovered, the common

law's "adversarial" tradition is not easily reconciled with the

"inquisitorial" (or investigative) approach of traditional civil law, and

conducting trials in which judges, prosecutors, and defendants come from

different countries (or legal cultures) poses a host of difficulties.

Nevertheless, there are some thirteen elements to trial

fairness about which there is a measure of consensus, and being afforded

the choice to defend yourself when a trial is essentially adversarial in

nature is almost universally recognized. Among the other twelve (often

expressed in the language of "fundamental human rights") there is at least

some agreement that to be "fair": (1) a trial should presume the defendant

is innocent and treat him accordingly; (2) the trial should be limited in

its subject matter by an indictment that clearly sets out the charges

against the defendant and specifically spells out both what conduct of his

was criminal and what laws were thereby broken; (3) the defendant should

have the opportunity to be present at the proceedings; (4) his trial

should be conducted in public; (5) he should be allowed a lawyer of his

own choice or provided competent appointed counsel if he cannot afford to

retain one (and all their dealings should be regarded as privileged, with

reasonable provision made for them to consult regularly throughout the

trial); (6) the defendant should neither be compelled to testify against

himself nor be coerced to confess prior to trial, but he must have an

opportunity to testify on his own behalf if he chooses to do so; (7) he

must be afforded the opportunity to confront and question witnesses

against him; (8) the court must ensure that some "equality of arms" exists

between the defendant's side and those prosecuting his case (in, for

example, their general level of resources and the time each side is

given); (9) the prosecution must provide the defense any exculpatory

evidence they discover in the course of their investigation or find

afterward to be in their possession; and (10), as a general matter, the

evidence against the defendant must have been obtained in a lawful manner,

given the circumstances of the case. After the trial is held, ( 11) the

judgment of the trial court must be written and must set out specifically

the facts and laws on which the court reached its conclusions; and,

finally (12), after the judgment is entered (or when necessary or useful

during the course of trial), provision must be made for appeal to a higher

court that is competent to address whatever legal issues the case may

implicate. As it happens, probably the most controversial topic in the

debate about trial fairness is whether to use a jury. My own view is that

in the context of very lengthy, complex cases, especially those that turn

on numerous difficult legal issues that involve little settled prior

precedent, the arguments against juries are compelling. Similarly, that

criminal trials be "speedy," another sacred idea, makes far less sense

when both sides will require months of preparation to be effective in

dealing with cases that are likely to involve hundreds of witnesses,

many thousands of pages of documents, and relatively untried areas of law.

2 Although Milosevic is acting pro se, he is

not unaided. Before the trial started, the prosecutors and the trial

judges assumed that Milosevic might very well sit mutely at his table

throughout the proceedings, a not unreasonable assumption given his early

statements that he regarded the court as "illegal." In their

determination that all relevant legal issues would be forcibly raised on

his behalf during the course of the proceedings, the trial chambers

appointed three seasoned attorneys (a British barrister, a Dutch

attorney who had tried several prior cases at the Hague, and a Yugoslavian

well acquainted with the complicated facts and politics of Yugoslavia's

war years). Nominally, the three were designated as amici curiae – or

friends of the court – who were expected to "assist" the court during the

trial, but in fact they have functioned, albeit with a measure of

restraint due to Milosevic's very active daily participation, as advocates

wholly on the side of the accused, and not as disinterested expert

advisers. In addition, Milosevic has two prominent Belgrade trial

attorneys designated as his "associates," with whom he evidently consults

after trial on a daily basis. Backed by their law firm's staff and, some

claim, sympathetic souls within the current Belgrade government's security

services, they prepare dossiers on prosecution witnesses, carefully sift

through the vast quantity of discovery materials supplied by the Office of

the Prosecutor, find news items relevant to events, and, some journalists

guess, also consult high-level Serb military and political figures with

personal knowledge of the particulars of a witness's testimony.

Nonetheless, Milosevic sits by himself at the defendant's table, and it is

likely he is purposefully trying to convey the impression that he is

acting entirely on his own, overmatched by the overwhelming resources of

what he calls "the Other Side." This tactic, of course, plays very nicely

into the Serb myth of the hero – stubborn, indomitable, and courageous,

particularly when faced with certain doom.

3 "Evidence," strictly speaking, is confined to the

testimony of witnesses under oath and documents introduced at trial to

the fact finder, whether judge or jury. The comments made by an advocate

in the course of trial are not "evidence" but are instead meant to be

regarded as no more than how a party to a proceeding would like the fact

finder to interpret the data presented. But in a recent order issued by

the Milosevic tribunal – ostensibly concerned only with procedure and the

mechanics of the defendant's upcoming presentation of his side of the

case-the court warned him that comments he might make in his advocate's

capacity concerning "facts" of the case would be "considered." What

exactly this means is, as yet, very much an open question.

4 International

Humanitarian Law, or IHL, suggests that the conduct of conflict of any

kind is of vital concern to us all, regardless of who is involved or where

it occurs. Many of those who work in IHL believe that the twentieth

century was by far the most brutal in recorded history, and feel that the

record of crimes committed by governments against civilians provides

strong evidence that IHL has been consistently violated "with

impunity" from its genesis in the mid-nineteenth century, when Europe's

Great Powers began to create rules and to write treaties in hopes of

making war more humane. Many advocates of IHL believe that it will

never be "law" until well-funded international institutions exist to

investigate, apprehend, and try those who commit major IHL crimes.

Critics of this vision, however, tend to dismiss IHL as being as

unrealistic as disarmament efforts before and after World War I or the

various attempts to declare war itself "unlawful." Regardless of your own

point of view on what is "law," you can be sure that the legal advisers to

armies and political leaders in the developed nations of the world are

going to be very careful readers of the Tribunal's jurisprudence for some

time to come.

5 The question of where or how IHL crimes ought to be

tried has long been a subject of debate. When the U.N. was first created

following the Second World War, it had been hoped that a permanent

criminal court could be established to carryon the legacy of the

war-crimes trials at Nuremberg. Such a court, it was thought, would be

the first step in creating "an enforcement mechanism" for a comprehensive

legal scheme to protect civilians in future from both the threat of

"total" war and any systematic domestic campaign of persecution. By 1993

this planned court had been stalled in obscure U.N. committees for a

little more than four decades, and the idea of setting up ad hoc forums

by using the Security Council's emergency powers was regarded as the only

way of cutting through the unavoidable red tape that pursuing the matter

in the General Assembly would have involved. A version of the original

U.N. plan, although no longer technically under the umbrella of U.N.

operations, has at last been realized in the International Criminal

Court, or ICC, created by a multinational treaty concluded in Rome in

1998. This treaty was ratified in record time, and the ICC currently has

ninety-two state parties, the United States conspicuously not among

them. Last spring the ICC appointed its first eighteen judges, and last

summer it swore in its first prosecutor and registrar.

6 The term "Genocide" was coined in the 1940s by one

Raphael Lemkin, a Polish legal crusader who lobbied tirelessly for what

became the U.N.'s 1948 Genocide Convention. The convention declared that

persecuting an ethnic or religious group with the object of destroying it

was subject to criminal punishment under during a time of conflict or

exclusively against a domestic population. The concept that "laws of

humanity and the dictates of the public conscience" applied to conduct

during conflict seems to have had its first formal recognition in the

preamble to The Hague Convention of 1907, "Respecting the Laws and

Customs of War on Land." The related term "Crimes Against Humanity" began

to gain currency during the Allies' discussions of the proposal, following

World War I, to try Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm before an international

tribunal of five judges for "a supreme offense

against international morality and the sanctity of treaties." "Grave

Breaches of the Geneva Conventions" were first defined in 1949 (in Article

147 of Convention IV), when, in the aftermath of World War II, the

treatment of civilians became an urgent concern among governments. These

breaches include, with qualifications, killing, torture (including

biological experimentation), deportation, confinement, compelling service

in the armed forces of a hostile power, taking hostages, the destruction

and appropriation of property, and depriving "a protected person" of the

right to a fair trial.

7 The term refers to legal principles that are

fundamental and well settled, and has come to mean what the law is rather

than what it should be. "Blackletter" derives from the custom of printing

medieval books in a heavy Gothic black type.

8 As anyone who remembers the Watergate scandal will

recall, the key questions were: What did Nixon know and when did he know

it? Obviously, when a superior explicitly orders a subordinate to commit a

crime, the matter of his guilt is fairly straightforward. But in many

situations common to criminal law and to civil liability as well, a

superior's culpability or vicarious liability is based on what he should

have reasonably done or known, regardless of what he did do or did know.

In consequence, he may be held responsible for what a subordinate does

that is ultra vires – beyond his power – and what, at least nominally, he

has expressly forbidden that subordinate to do. Although many legal

cultures speak of "facts" and "law" as existing at a remove from each

other, important questions can turn on their interrelation. If, in the

Milosevic case, the trial court determines that he personally directed a

decade of "ethnic cleansing" campaigns, the legal implications of the

court's decision may well prove much less far-reaching than if a

conviction turns primarily on the idea that either (1) he could have

stopped what was going on but failed to do so; or (2) regardless of what

he actually ordered or wished, he should be held personally and

criminally accountable because he possessed ultimate formal (de jure) or

actual (de facto) "command responsibility" for the acts of organized

armed forces that he and his government supported and "controlled" in only

a general way. Such an outcome would be a source of considerable anxiety

to almost every national leader on earth.

9 The main thrust of Tadic's strategy was simple

alibi, and he contended throughout his trial that prosecution witnesses

had wrongly identified him, or that he was never present at any of the

crimes they described.

Following the Tadic trial, both sides appealed. The Appellate

Chamber's decision is especially significant in its discussion of whether

the conflict in Bosnia was "internal" or "international" for purposes of

determining the application of the 1949 Geneva Conventions' "Grave

Breaches" provisions. The trial court had decided that the conflict was

"international" up until May 1992 and "internal" thereafter. This

conclusion was premised on Belgrade's formal "withdrawal" of its armed

forces, the JNA, from Bosnia in response to an ultimatum issued by the

U.N. Security Council. The withdrawal, however, took place mainly on paper

and consisted of dividing the JNA into a Serbian "VJ" and a legally

distinct Bosnian Serb "VRS" army. In reality, the men and the weapons

Belgrade had sent to Bosnia remained, and virtually the only change was

one of name and uniform.

10 Each year, one task

of the Tribunal's president – a judge, elected, for a two-year term,

by his or her peers – is to write an annual report addressed to both the

U.N. Security Council and the General Assembly. Reports from the

Tribunal's early years in operation are instructive, and the first

year's report especially is both candid and surprisingly plaintive. The

Security Council's commitment to making the Tribunal a robust entity

with a staff and resources adequate to perform its job appears, in

retrospect, to have been decidedly halfhearted. Initially, the

Tribunal was funded in six-month cycles, with an initial start-up

commitment of just $5.6 million for the January to June 1994 period.

Evidently, the choice of a six-month fiscal period had the unfortunate

consequence of preventing the Tribunal from signing a lease on

property for a headquarters and proved a serious impediment to

recruitment, since no contract for more than half a year could be

promised to anyone. By the Tribunal's second year, much of this had been

sorted out, and its overall funding had been increased to more than $25

million a year, with authorization for some 260 posts. But initially,

the charity of a number of states making "voluntary contributions" had

been crucial. The United States supplied the Office of the Prosecutor

with a $2.3 million computer system and temporarily reassigned

twenty-two professional staff members to work without salary from the

Tribunal for up to two years. Other nations joined in with similar

offers of voluntary staff and gifts in kind, while some, including

Malaysia and Pakistan, which both had judges appointed to serve at the

Tribunal, sent cash (in the amounts of $2 million and $1 million,

respectively). At present, the Tribunal's annual budget is in the region

of $125 million a year, a very significant share of the U.N.'s

non-peacekeeping expenditure. And the Tribunal's staff has grown to some

1,300, who come from eighty-three different U.N. member states.

11 Much has been written of late about bringing

Hussein and his top lieutenants to trial as "war criminals," presuming of

course they are captured alive. Those who have some say in the matter

would do well to study the Milosevic proceedings. The several years of

both direct and indirect preparation involved in, for example, marshaling

adequate admissible evidence and finding witnesses is but one- issue.

Others include whose notion of a "fair" trial will prevail, and whether

the trial is to deal with almost twenty-five years of International

Humanitarian Law and human-rights abuses or ought to be a brief proceeding

limited in its scope. If the latter, victims' families are certain to

raise passionate objections. A trial of broad scope, on the other hand,

would undoubtedly drag on for several years. And it is quite easy to

imagine that much would be made of active U.S. support of Hussein's regime

during the country's conflict with Iran, that the "legality" of the United

States invasion would be vigorously contested by the defendant(s), and

that every effort possible would be made to play to the region's

anti-American audience, portraying Hussein as both a martyr struggling to

defend Islam from the West and something of a pawn, turned upon and

betrayed by his former ally, the United States. Doubtless, too, some

attempt would be made not only to portray the current Bush agenda for the

Middle East in a sinister light but also to implicate the United States

during the period prior to Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, perhaps even in the

role of an accomplice that supplied and trained Hussein's armed forces

while turning a blind eye to IHL crimes they were fully aware of and might

have done something to prevent.

12 The Peace Palace fulfills the Victorian era's canon

that it is always a good idea to decorate the decoration. The building,

which was inaugurated with great fanfare on August 28, 1913, required

almost ten years to complete and was to be the seat of the Permanent Court

of Arbitration, which was created under the auspices of The Hague Peace

Conference of 1899 and its Hague Convention I, "For the Pacific Settlement

of International Disputes." The building's costs were paid in their

entirety by the Scottish-American steel magnate turned philanthropist

Andrew Carnegie, who had an unshakable faith in what was once termed

"progress" and believed the inexorable path of humanity toward perfection

was as incontestably part of the scheme of things as Darwin's law of

natural selection. Peace was Carnegie's great cause in his later years,

and the "Temple of Peace" at The Hague was only one of three he managed to

complete before the outbreak of World War I's hostilities suggested that

progress toward perfection might not be quite so inexorable as all that.

13 To give one example, the International Military

Tribunal for the Far East, as it was' called, was made up of eleven

judges, drawn from each of the countries involved in that theater of

conflict. It was a complex case brought against twenty-eight high-ranking

Japanese defendants, and the proceeding, described at the time as "the

biggest trial in recorded history," lasted from April 1946 until November

1948. Since the judges were not required to attend the proceedings on a

daily basis (and many chose not to, even for weeks at a stretch), the

Tribunal's rulings on crucial questions like the admissibility of evidence

demonstrably varied from day to day, depending entirely on which judges

were or were not present. In the end, five of the eleven judges

wrote dissenting or partially dissenting opinions. Astonishingly, the

Tokyo judgment remained unpublished until 1977 (when it appeared in an

Amsterdam university press monograph). Prior to 1977, the majority opinion

and five dissents could be read only by seeking out a handful of surviving

stenciled copies.

14 At present, the expectation is that the Tribunal

will not wind up its affairs before 2012. If its present docket and annual

budget are projected forward, it is not unreasonable to guess that at the

end of its eighteen years in existence the Tribunal will have tried

approximately 100 cases at a total cost of more than $1.5 billion. This

figure provides at least some sense of the scale and cost of what it is

possible for an international criminal tribunal to do. Today the

prevailing view among prosecutors and others with whom I've spoken is that

before indictments are sought it is essential to understand a conflict as

a whole and only then to target those who have played the largest part or

most crucial roles in events. To deal with the many thousands of other

potential defendants, rebuilding, or helping to create, smoothly

functioning domestic courts is an essential task that must be part of the

larger picture with which the international community is concerned.

15 In addition to the live broadcast feed to the

Internet, there is a daily archive of the feed compiled by Bard College

that can be readily accessed by the public, and at least one U.S.

university is compiling video archives of all the Tribunal proceedings.

Roughly a dozen journalists regularly use the press room in the Tribunal

building, the majority of whom are from dailies of the former Yugoslavia.

16 In terms of the typical relationship between trial

courts and courts of appeal (which are charged with deciding, among other

matters, if the trial below was conducted fairly), the trial court's

opportunity to assess demeanor is often key. For example, in the federal

court system of the United States, and in most state courts as well,

except in the most unusual circumstances (or when confronted by the most

blatant sort of error), appellate courts defer completely to whatever

"facts" the trial court has determined. Part of the basis of this policy,

as it is routinely justified, is that trial judges have actually seen and

heard the witnesses, and transcripts can never adequately convey enough

about the person on the stand for anyone who wasn't present to confidently

second-guess those who were.

17 Whether and in

what ways this matters is a question that goes to the root of how IHL

trials are or should be different from garden-variety criminal ones. If

the goal is, as it was at Nuremberg, to assemble a somewhat complete

historic record of events, create a comprehensive documentary archive for

posterity, and vindicate the stories of survivors and victims that had

seemed too horrible to be plausible, then strict time limits are a major

failing. If the idea is primarily, as one seasoned American ICTY

prosecutor phrased it, "to get the bad guy," then a conviction on one

count, which results in a life sentence, is as good as a conviction for

sixty-six counts.

18 "Bibs" and

robes are required for counsel making court appearances. To buy, bibs cost

an astonishing 450 euros but may be rented from the Tribunal at 150 euros

a month (with an option to purchase).

19 In major American criminal trials, in contrast to

British practice, prosecution witnesses typically undergo extensive

"preparation," or rehearsal, so that there will be few surprises when they

testify, both on direct examination and subsequent cross-examination. The

OTP does not seem to have a clear policy on whether such preparation is

important, in accordance with the American view, or wholly improper, in

line with British thinking. What is clear is that in most trials at the

ICTY, at least some of the live witnesses either have not been entirely

candid about themselves with the lawyers who have called them to testify

or have changed their stories in unexpected ways from an earlier version.

To a certain extent, even in legal systems where trial preparation is

extensive, this is a problem that a seasoned trial attorney must allow

for. But at the Hague, three factors aggravate the situation. First, the

problem of witness intimidation has not been wholly solved by the ICTY's

efforts at witness protection; second, the OTP, and often defense teams

too (particularly that assisting Milosevic), have become remarkably

skillful at rapidly assembling detailed personal dossiers about witnesses

that frequently contain unflattering information useful to undermining

"credibility" on cross-examination; and third, given the horrific events

involved, and the fact that many who have lived to tell their tale were

not disinterested bystanders, Tribunal trial judges often have the

unenviable task of deciding how much to accept the truthfulness of a

witness who is plainly lying about, or at the least minimizing, his own

role. These problems are important to note, especially in the context of

the ICTY's debate over using written statements as a time-saving

alternative to live testimony.

20 A visit to SlobodanMilosevic.org, which offers a

daily summary of the trial, is instructive. For example, their view of a

recent day of "crime-based" testimony attacks May as being both unfair and

incompetent: "After President Milosevic had explained, to this pathetic

excuse of a 'judge,' the concept of 'innocent until proven guilty,' which

appears to be completely foreign to 'Dick' May, Mr. Tapuskovic [one of the

trial's amici] had to explain to this idiot what his job was in the first

place. Mr. Tapuskovic explained to that crimson robe-wearing fool that as

a judge his job is to sit and listen to the evidence and then decide,

after hearing all of the evidence, if the witness is telling the truth or

not."

21

In the United

States, allowing cameras into courtrooms has fired contentious debate

since the rise of television and the advent of modem mass media in the

1950s. One scholar I spoke to, who has watched the Tribunal with interest

since its founding, felt strongly that cameras in courtrooms profoundly

affect proceedings. His view is that when people know there is a camera

present, they can't help but perform. There may be some truth to this. I

have difficulty, however, discerning much difference between the effect of

the presence of cameras and that of what might be called "a live studio

audience."

22

In common law, in a criminal trial before a jury, the submission

of evidence follows strict rules. In a U.S. criminal trial, the

Fourth Amendment prohibition against "unreasonable searches and seizures"

can be of crucial importance, and the twentieth-century judicial

enforcement mechanism by which evidence can be excluded from consideration

if obtained by prosecutors illegally is popularly known as the "fruits of

the poison tree" doctrine. Accordingly, in a U.S. trial where wiretap

evidence is offered, an able defense lawyer typically hones in on the

question of where, how, by whom, and under what legitimating authority

recorded intercepts of a defendant's telephone conversations were

obtained.

|